by Rusty Slade

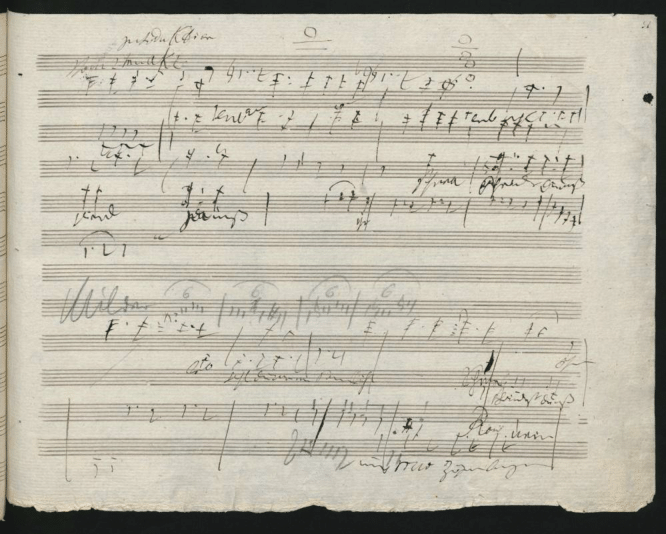

A page from Beethoven’s sketchbook scanned by Giovanni Tribuzio accessed via IMSLP – public domain

On May 14th, 2025, during a sunny afternoon, I received my diagnosis for ADHD. ADHD had been something that I suspected I had but never confirmed. I remember discussing with my mother during a car ride from school (nearly a decade before) that I couldn’t listen to my English teacher. Despite my best efforts, I couldn’t direct my focus where it needed to go. I thought to myself: am I just dumb? Am I the only one struggling with this? I said to her, “I think something is wrong with me.” My mother shrugged it off and told me it’s normal. That everyone struggles to focus sometimes. “You’ll be fine.”

But what is ADHD?

By now it has become common knowledge that ADHD stands for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The DSM 5 classifies it as a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by “a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development, as characterized by inattention and/or hyperactivity.” Over the years, the terms have changed. The most common terms, before ADHD, was Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD).

While that definition is dry, let me explain it by moving ADHD into the horribly arid cooperate-office climate. Inattention in the wild (the office or grey cubicle) looks like forgetting the instructions your boss gave you (even though it’s in an email and she explained it twice already), piles of papers everywhere (where was that invoice?), and “weren’t you supposed to return that call an hour ago?” ADHD can be ruthless. Relentless distractions, tasks, lack of focus, forgetfulness, daydreaming, reluctance to try hard things, and a lack of follow-through are the hallmarks of inattentive ADHD.

On the other side of ADHD is hyperactivity-impulsivity. This is part of the more familiar view of ADHD. This includes that classmate that is always goofing off or whispering quips. A person who can’t sit still. A person who talks without end. The impulsive part may look like a person with no filter, or who doesn’t think twice. Or perhaps someone who gets hooked on TV shows and binges them till 3 am. There are many aspects of ADHD that all get lumped into a single label, but the key aspects are distractibility, inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness.

Getting my diagnosis for ADHD was simple, once I got to it. I made a psychiatry appointment at a mental health center, put it in my calendar so I wouldn’t forget, and showed up. I filled out a questionnaire on a tablet in the lobby that asked a lot of questions about my symptoms, the severity of my symptoms, and how long I have experienced them. After an interview with my nurse-practitioner, he was able to determine that I have ADHD.

ADHD affects every aspect of my life, but as a musician it corrodes the daily nuts and bolts of learning, practicing, and performing. Every musician strives to find the bets way to spend their practice time, but musicians with ADHD face additional challenges. Researchers Pheobe Saville, Caitlin Kinney, Annie Heiderscheit, Hubertus Himmerich wrote the article “Exploring the Intersection of ADHD and Music: A Systematic Review.” In this review, they analyzed 20 research projects from between 1981 and 2023. Although they admit the amount of data is small, it points toward some unexpected results with how ADHD and music interact. An article by Erin J. Hopkins published in the “Journal of Music Teacher Education” in 2025 also outlines strategies for music educators with ADHD that musicians can also use to improve their careers.

To illustrate how impulsivity and inattention can affect performance and practice, I’d like to give an example of one of my more embarrassing rehearsal experiences. During this orchestra rehearsal I failed to execute a syncopated passage several times (syncopated meaning playing during off-beats). No one wants to be the only one playing during a rest. While inattention and impulsivity are the main culprits, the article by Saville et. al goes further. According to the research, individuals with ADHD may struggle with timing and guessing short time intervals (key factors for rhythm). The researcher’s analysis of previous studies found that: “Children with ADHD performed worse in estimating short time intervals,” “children with ADHD perceived tracks as longer when the musical notes had longer durations,” and “adults with ADHD had deficits in the perception of complex music.”

This review by Savill et. al shows that musicians with ADHD might have an initial disadvantage developing skills in “rhythm, timing, and beat synchronization” as well as “performance in musical perception tasks.” That syncopated passage was an example where I struggled more than my peers because of my disability. I had to compensate with additional practice, work, and stress (the very real cost of a learning disability).

Now let’s look at my education and how the symptoms of my ADHD presents challenges outside of performance and practice.

As a music major, my training consists of book stuff and performing stuff. The “book stuff” is mostly music theory and history. This is where the classroom struggles with ADHD occur. Even though I enjoy learning music theory, I’ve experienced friction with ADHD. Reading materials, worksheets, exercises, essays, studying, and lectures are difficult to get through. My inattentiveness is a major obstacle in the way of accomplishing these tasks. I’ve been told “Can anyone, other than Rusty, tell me what this chord is?” because I have trouble raising my hand before I speak or giving the answer before the question is asked. I’ve also had my fair share of zoning out or daydreaming during lectures, followed by scrambling to google the information later.

Like many of my classmates, I also procrastinate on my work. However, my procrastination is too severe for me to leave it alone. It can get out of control rapidly. Even when I set up a time and place, say at the library at 4 pm, I cannot rally my attention. Getting work done usually is a balance of waiting for the deadline to get close enough to feel the pressure, but not so close I choke.

However, there are some advantages to ADHD as well. Edward M. Hallowell and John J. Ratey in their book about ADD and ADHD “Driven To Distraction” outline four qualities that people with ADHD have that can enhance creativity, which can be an essential skill for musicians.

Hallowell and Ratey explain, “people with ADD have a greater tolerance of chaos than most.” Because ADHD lends itself toward disorganized and chaotic environments, when the creative process gets messy they can handle it. Composing the development of a sonata-form (a musical structure primarily used during the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe) is one such example. The process of breaking down musical ideas and combining them in new ways to create drama or interest might be messy, but that is also what makes it fun.

Hallowell and Ratey continue with their second point, “What is creativity but impulsivity gone right?” Acting on impulse and disregarding barriers gives people with ADHD a creative advantage. Without second-guessing, creativity can be freer and more abundant or lead to ideas that don’t get immediately discredited. For example, I keep a midi keyboard on my desk so that when ever I have an idea I can play it back and record it immediately. It allows me to act on my impulse and takes advantage of one of my creative strengths.

Another quality of ADHD that can enhance creativity, the third point Hallowell and Ratey give, “is the ability to intensely focus or hyperfocus at times.” When it comes to ADHD, getting “in the zone” can be the most difficult part of life. It’s a battle in your mind to get the engine going, but when it does it is a cruise. This can require certain catalysts, like stress, adrenaline, caffeine, or medication. Reaching a state of hyperfocus is rewarding and effective. It can make ADHD feel like a superpower, or a secret weapon for productivity when it is utilized correctly.

The fourth element that Hallowell and Ratey outline is the “hyperreactivity” that people with ADHD have. Because they are always reacting, novel combinations of ideas are possible and occur frequently. This particular quote from Hallowell and Ratey explains it eloquently, “Each collision has the potential to emit new light, new matter, as when subatomic particles collide.” Because I keep a midi keyboard at my desk, I give myself the opportunity to react to what I hear. I digest what I listen to, whether it is the rhythms of human speech or the contour of birdsongs.

Compensating for ADHD can be difficult. Erin J. Hopkins’ article “Perspectives and Expertise of Secondary Ensemble Music Educators With ADHD” published in the “Jounral of Music Teacher Education” (2025) interviewed three music educators with ADHD to learn how they accommodate for their own ADHD and ADHD in their students.

Some of the key insights from Hopkins’ interview with the first educator expressed that educating about ADHD is a key component when advocating for ADHD. In the interview, she said “our brains are just wired differently and that is what allows us to be more creative…This is what makes us unique.” Communicating that message, communicating what ADHD is, is essential for getting accommodation.

For example, “so you’re just are lazy,” is something I’ve been told that directly relates to the symptoms of my ADHD. This stigma associated with ADHD is false, it often takes more work to accomplish the same tasks. Advocating for ADHD is about addressing these stigmas and working with people to implement solutions. I am not lazy. However, I do need to set reminders, receive encouragement, and create incentives. Without education, without discussion, without conversation those changes don’t happen.

The second educator from Hopkins’ article advocated for the power of intrinsic motivation. Utilizing personal motivations (rather than impersonal ones) makes the task something the ADHD person wants to do, rather than something they must do but can’t find the energy for. Giving the right amount of freedom, agency, and incentive for the individual with ADHD can unlock the power of intrinsic motivation and utilize their dormant strengths.

The third educator that Hopkins interviewed used “proactive strategizing” to get ahead. By staying organized and ahead of tasks, lesson planning, and emails she prevents her ADHD from getting in the way of her duties and deadlines. One of the key aspects of treatment is structure, according to Hallowell and Ratey. Treating ADHD with structure, like the third educator did, allows people with ADHD to get more done and prevent conflicts.

Understanding the challenges of ADHD and providing empathetic approaches to accommodation are essential for building a supportive network for success. Education, intrinsic motivation, and proactive strategizing are three ways to harness the unfulfilled potential of the ADHD brain, ways to restructuring around it and not against it.

When I shared my diagnosis with my family, there was no surprise. Almost all of my immediate family had seen the symptoms and suspected I had ADHD before my official diagnosis. After my diagnosis, I made changes to my life’s structure, like those music educators in Hopkins’ article, like Hallowell and Ratey suggested. I identified my weaknesses and worked hard to compensate, or find solutions. I feel satisfied knowing what I am capable of. I feel better about myself. I know I am not dumb, only wired differently, and I can use that to my advantage. ADHD doesn’t have to be a struggle.