Kathryn Schulz’s “The Really Big One,” a Pulitzer-prizing winning article, is compelling for the shocking science involved and for the vivid storytelling techniques Schulz uses. Schulz makes the writing masterful in three concrete ways.

First, Schulz immediately draws me into the story because it starts in media res, which means in the middle of things, a well-known technique in storytelling that situates readers immediately in time and place and tends to pique readers’ interest.

Her first two sentences describe paleoseismologist Chris Goldfinger at a seismology conference in Kashiwa, Japan, who is coincidentally experiencing an earthquake. The scientists laugh a bit at first due to the irony of being at a conference about earthquakes while experiencing an earthquake, but the moment turns somber quickly. Apparently, the longer the earth shakes, the more serious is the earthquake.

Minute by minute Shulz describes Goldfinger’s thought process switching between awe to rising alarm. Finally, she relates the aftermath: “In the end, the magnitude-9.0 Tohoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami killed more than eighteen thousand people, devastated northeast Japan, triggered the meltdown at the Fukushima power plant, and cost an estimated two hundred and twenty billion dollars.”

Schulz’s narrative ability is masterful, demonstrating how slowing down the narrative and describing events in detail can persuade readers to keep reading.

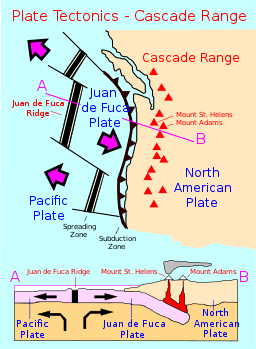

The second way that Schulz teaches me to write in a more compelling and concrete manner is when she describes the Cascadia subduction zone. She commands her reader: “Take your hands and hold them palms down, middle fingertips touching.” Then, she describes how readers should move their hands to represent how plates inside the earth will eventually move, ending with: “That’s the very big one.” Of course, that is the title of the entire article, referring to an seismic event that will devastate a huge portion of North America.

User:Surachit is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

It is a rare thing for a writer to command the reader to do anything physical when reading, but moving my hands in the ways she describes helped me to understand the concepts in a much more concrete way. For me, the technique Schulz uses is brand new, but is an idea I can tuck away in my writer’s toolkit for future use.

The final masterful technique that Schulz uses is her ability to weave compelling and vivid imagery into an otherwise science-focused article. In the final paragraph, for instance, Schulz describes an office “deep inside the induction zone,” the zone that will be demolished when the Cascadia fault line moves. She writes, “All day long, just out of sight, the ocean rises up and collapses, spilling foamy overlapping ovals onto the shore.” The scene is serene and beautiful but ends on an ominous note. “Eighty miles farther out,” Schulz writes, “ten thousand feet below the surface of the sea, the hand of a geological clock is somewhere in its slow sweep.” In other words, disaster is inevitable, time is running out, and Schulz’s compelling descriptions underscore the terrible severity of a catastrophe that will break off a large, well-occupied chunk of North America. We can only hope “the really big one” won’t happen anytime soon.